TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2022

Development prospects in a fractured world: Global disorder and regional responses

4

A. TOO CLOSE TO THE EDGE

1. A year of serial crises

After a rapid but uneven recovery in 2021, the world economy is in the midst of cascading and

multiplying crises. With incomes still below 2019 levels in many major economies, growth is slowing

everywhere. The cost-of-living crisis is hurting the majority of households in advanced and developing

countries. Damaged supply chains remain fragile in key sectors. Government budgets are under

pressure from scal rules and highly volatile bond markets. Debt-distressed countries, including

over half of low-income countries and about a third of middle-income countries, are edging ever

closer to default. Financial markets are jittery, as questions mount about the reliability of some asset

classes. Thevaccine roll-out has stalled, leaving vulnerable countries and communities exposed to

new outbreaks of the pandemic. Against this troubling backdrop, climate stress is intensifying, with

mounting loss and damage in vulnerable countries who lack the scal space to deal with disasters, let

alone invest in their own long-term development. In some countries, the economic hardship resulting

from these compounding crises is already triggering social unrest that can quickly escalate into political

instability and conict.

The resulting policy challenges are daunting, especially in an international system marked by rising

distrust. At the same time, the institutions of global economic governance, tasked since 1945 with

mitigating global shocks, delivering international public goods and providing a global nancial safety

net, have been hampered by insufcient resources and policy tools and options that are “rigid and

old fashioned” (Syed, 2022; Yellen, 2022). Even as growth in advanced economies slows down more

sharply than anticipated in last year’s Report, the attention of policymakers has become much too

focused on dampening inationary pressures through restrictive monetary policies, with the hope that

central banks can pilot the economy to a soft landing, avoiding a full-blown recession. Not only is

there a real danger that the policy remedy could prove worse than the economic disease, in terms

of declining wages, employment and government revenues, but the road taken would reverse the

pandemic pledges to build a more sustainable, resilient and inclusive world (chapter III).

As noted in last year’s Report, the pandemic caused greater economic damage in the developing world

than the global nancial crisis. Moreover, with their scal space squeezed and inadequate multilateral

nancial support, these countries’ bounce back in 2021 proved uneven and fragile, dependent in

many cases on a further build-up in external debt. The immediate prospects for many developing and

emerging economies will depend, to a large extent, on the policy responses adopted in advanced

economies. The rising cost of borrowing and a reversal of capital ows, combined with a sharper than

expected slowing of China’s growth engine and the economic repercussions from the war in Ukraine,

are already dampening the pace of recovery in many developing countries, with the number of those

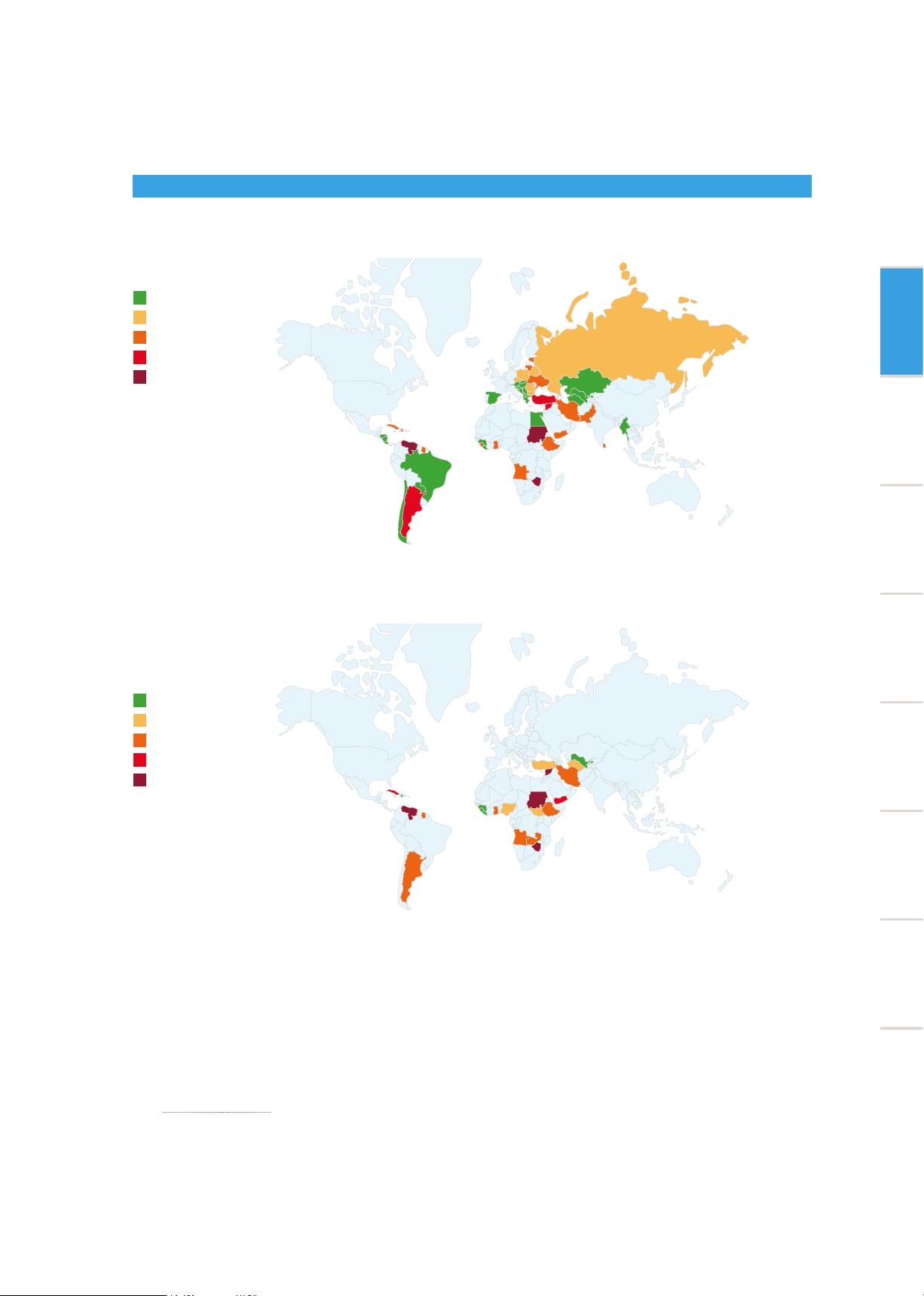

in debt distress rising, and some in default. With 46 developing countries already severely exposed to

nancial pressure from the high cost of food, fuel and borrowing, and more than double that number

exposed to at least one of those threats, the possibility of a widespread developing country debt

crisis is a very real one, evoking painful memories of the 1980s and ending any hope of meeting the

sustainable development goals (SDGs) by the end of the decade.

The acceleration of ination beginning in the second half of 2021 (gure 1.1) and continuing even as

economic growth began to slow down in the nal quarter of the year has led many to draw parallels

with the stagationary conditions of the 1970s. Despite the absence of the wage-price spirals that

characterized that decade, policymakers appear to be hoping that a short sharp monetary shock –

along the lines, if not of the same magnitude, as that pursued by the United States Federal Reserve

(the Fed) under Paul Volker – will be sufcient to anchor inationary expectations without triggering

recession. Sifting through the economic entrails of a bygone era is unlikely, however, to provide the

forward guidance needed for a softer landing given the deep structural and behavioural changes that

have taken place in many economies, particularly those related to nancialization, market concentration

and labour’s bargaining power.

我的内容管理

展开

我的内容管理

展开

我的资源

快来上传第一个资源

我的资源

快来上传第一个资源

我的收益 登录查看自己的收益

我的收益 登录查看自己的收益 我的积分

登录查看自己的积分

我的积分

登录查看自己的积分

我的C币

登录后查看C币余额

我的C币

登录后查看C币余额

我的收藏

我的收藏  我的下载

我的下载  下载帮助

下载帮助

前往需求广场,查看用户热搜

前往需求广场,查看用户热搜

信息提交成功

信息提交成功