没有合适的资源?快使用搜索试试~ 我知道了~

资源推荐

资源详情

资源评论

American Economic Association

Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information

Author(s): Joseph E. Stiglitz and Andrew Weiss

Source:

The American Economic Review,

Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jun., 1981), pp. 393-410

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1802787 .

Accessed: 09/09/2014 11:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

American Economic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 173.219.185.130 on Tue, 9 Sep 2014 11:54:41 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Credit

Rationing

in

Markets

with

Imperfect

Information

By

JOSEPH

E. STIGLITZ

AND ANDREW WEISS*

Why is

credit

rationed?

Perhaps the

most

basic tenet

of economics

is that

market equi-

librium

entails

supply

equalling

demand;

that

if demand

should

exceed

supply,

prices

will

rise, decreasing

demand

and/or

increasing

supply

until

demand

and

supply

are

equated

at the

new

equilibrium

price.

So if prices

do

their job,

rationing

should not

exist.

How-

ever,

credit rationing

and

unemployment

do

in fact exist.

They seem

to

imply an

excess

demand

for

loanable funds

or an excess

supply

of workers.

One method

of

"explaining"

these

condi-

tions

associates them

with short-

or long-term

disequilibrium.

In the short term they

are

viewed

as

temporary

disequilibrium

phenom-

ena; that

is, the

economy

has incurred

an

exogenous

shock,

and

for

reasons

not fully

explained,

there

is some stickiness

in

the

prices

of

labor

or capital

(wages

and

interest

rates)

so that there

is

a

transitional

period

during

which

rationing

of

jobs

or credit

oc-

curs.

On

the

other

hand,

long-term

un-

employment

(above

some "natural

rate")

or

credit

rationing

is

explained

by governmen-

tal

constraints such

as

usury

laws or

mini-

mum

wage

legislation.'

The object

of this paper

is

to show

that

in

equilibrium

a loan

market

may

be char-

acterized

by

credit

rationing.

Banks making

loans

are concerned about

the interest

rate

they receive

on the loan,

and the riskiness

of

the

loan.

However,

the

interest rate

a bank

charges

may itself

affect the

riskiness of the

pool of

loans by

either: 1) sorting

potential

borrowers

(the

adverse selection

effect);

or

2)

affecting

the actions of

borrowers (the

incen-

tive effect).

Both effects derive directly

from

the

residual

imperfect

information

which

is

present

in loan markets

after banks

have

evaluated

loan applications.

When

the price

(interest

rate) affects the

nature of

the trans-

action,

it

may not

also clear

the

market.

The adverse

selection

aspect

of

interest

rates is a

consequence

of different

borrowers

having different

probabilities

of

repaying

their

loan.

The

expected

return to the bank

obviously

depends on

the probability

of re-

payment,

so the bank

would

like

to

be able

to identify

borrowers who are more likely to

repay. It

is difficult to

identify

"good bor-

rowers,"

and to do so

requires the

bank to

use

a

variety

of

screening

devices.

The

inter-

est

rate

which an individual

is

willing to pay

may

act as one such screening

device: those

who are

willing to pay

high interest

rates

may,

on

average,

be worse risks;

they

are

willing to

borrow at

high interest

rates be-

cause they perceive

their

probability

of

re-

paying

the

loan

to

be low.

As

the interest

rate rises,

the average

"riskiness"

of those

who borrow increases,

possibly lowering

the

bank's

profits.

Similarly,

as the interest rate

and other

terms of the contract change,

the

behavior of

the borrower

is

likely

to

change.

For

in-

stance,

raising the

interest rate decreases

the

return

on projects

which succeed.

We

will

show

that higher interest

rates

induce firms

to undertake

projects

with

lower

probabili-

ties

of

success but

higher payoffs

when suc-

cessful.

In a

world with

perfect

and costless

infor-

mation,

the

bank would

stipulate

precisely

all

the

actions

which

the

borrower

could

*Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc. and Princeton

University, and

Bell

Laboratories, Inc., respectively.

We

would like to thank Bruce Greenwald, Henry Landau,

Rob Porter, and Andy Postlewaite for fruitful comments

and suggestions. Financial support

from the National

Science

Foundation is

gratefully acknowledged.

An

earlier version of this

paper

was

presented

at the

spring

1977 meetings of the Mathematics

in

the Social Sciences

Board

in

Squam Lake, New Hampshire.

'Indeed,

even if markets were not competitive one

would not expect to find rationing; profit maximization

would, for instance, lead a monopolistic bank to raise

the interest rate it

charges

on loans to the

point

where

excess demand for loans was eliminated.

393

This content downloaded from 173.219.185.130 on Tue, 9 Sep 2014 11:54:41 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

394

THE

AMERICAN

ECONOMIC

REVIEW

JUNE

1981

z

m

1Z

w

I- /

0

a-

2

@ -

w

w

w

r

INTEREST

RATE

FIGURE

1.

THERE EXISTS

AN

INTEREST

RATE

WHICH

MAXIMIZES

THE

EXPECTED RETURN TO THE

BANK

undertake

(which might

affect the

return

to

the

loan). However,

the

bank is

not able to

directly

control

all the

actions of the bor-

rower; therefore,

it will

formulate the terms

of

the

loan contract

in

a manner

designed

to

induce

the borrower to take actions which

are

in

the interest

of

the

bank,

as

well as to

attract

low-risk

borrowers.

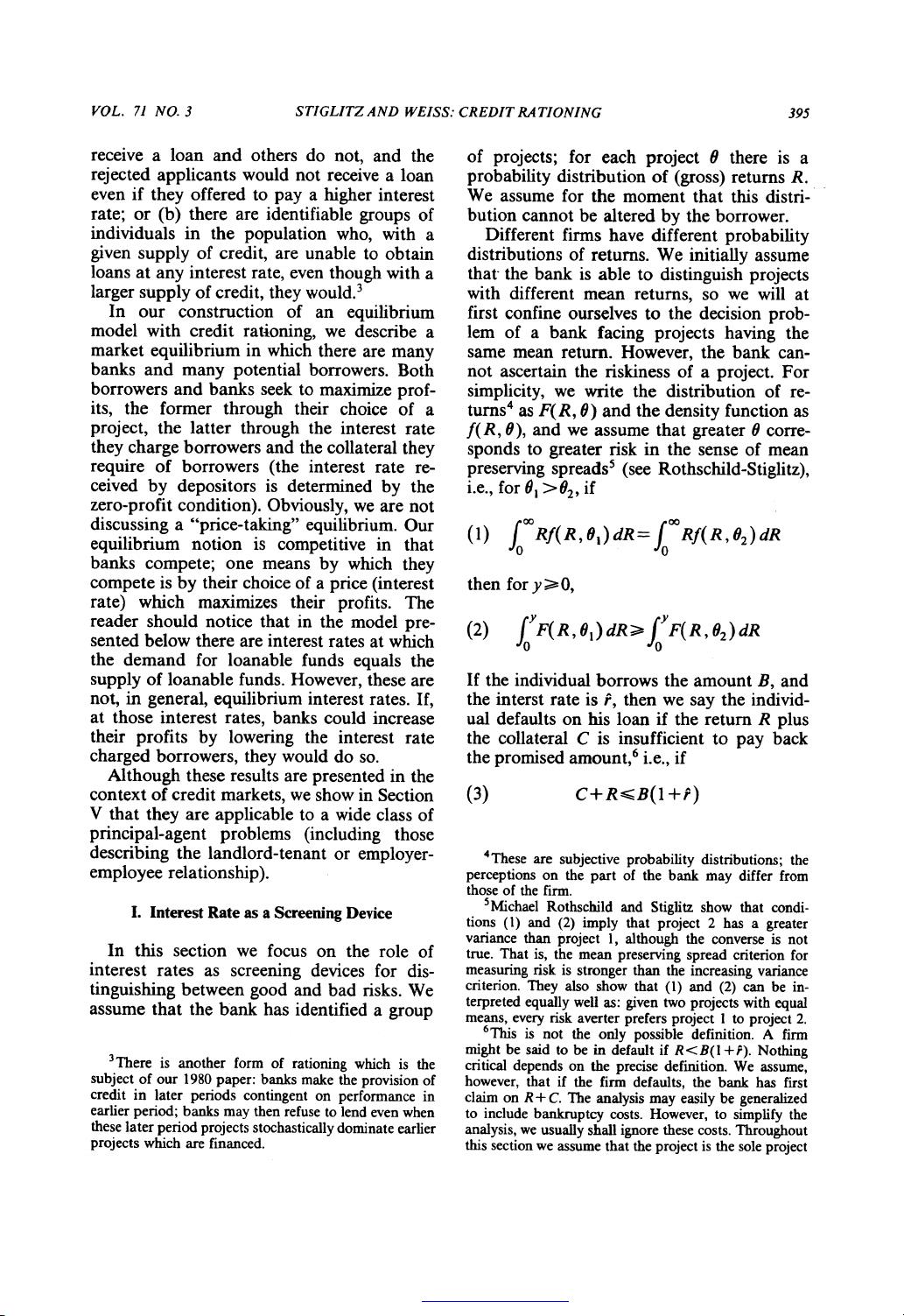

For both

these

reasons, the expected

re-

turn

by

the bank

may

increase

less

rapidly

than

the

interest

rate; and, beyond

a

point,

may actually decrease,

as

depicted

in

Figure

1.

The interest rate at

which the

expected

return to

the

bank

is

maximized, we refer to

as the

"bank-optimal" rate, Pr.

Both the demand

for

loans and the

supply

of funds

are functions of the

interest rate

(the

latter

being

determined

by

the

expected

return

at

r*). Clearly,

it is

conceivable that at

r

the

demand for funds exceeds the

supply

of

funds.

Traditional

analysis

would

argue

that,

in

the

presence

of an

excess demand for

loans,

unsatisfied borrowers

would

offer

to

pay

a

higher

interest rate

to the

bank,

bid-

ding up

the interest rate until

demand

equals

supply.

But

although supply

does not

equal

demand at

r*,

it

is

the

equilibrium

interest

rate! The

bank

would not

lend

to

an

individ-

ual who

offered

to

pay

more

than

r*.

In

the

bank's

judgment,

such a loan

is

likely

to be a

worse

risk

than the

average

loan

at

interest

rate

P*,

and the

expected

return to a

loan at

an interest rate

above

r*

is

actually

lower

than

the

expected return to the loans the

bank

is presently making. Hence, there are

no competitive

forces leading supply to equal

demand, and

credit is rationed.

But the

interest rate

is

not the only term of

the contract

which

is

important.

The

amount

of the loan,

and the amount of collateral or

equity the bank demands of loan

applicants,

will also affect

both the behavior of bor-

rowers and

the

distribution

of

borrowers. In

Section III,

we

show that

increasing

the

col-

lateral requirements

of lenders

(beyond some

point) may

decrease the

returns

to the

bank,

by

either

decreasing

the

average degree of

risk

aversion of

the pool

of

borrowers;

or in

a

multiperiod

model inducing

individual in-

vestors to

undertake riskier projects.

Consequently,

it may

not be

profitable to

raise

the interest

rate

or

collateral require-

ments when a

bank has an excess demand

for

credit;

instead,

banks

deny

loans to bor-

rowers

who are

observationally indis-

tinguishable from

those who receive loans.2

It is not our

argument that credit rationing

will always

characterize capital markets, but

rather that it

may occur

under

not implausi-

ble

assumptions concerning borrower and

lender behavior.

This

paper

thus

provides

the first

theoret-

ical justification

of

true

credit

rationing.

Pre-

vious studies have

sought

to

explain why

each individual

faces

an

upward sloping

in-

terest

rate

schedule.

The

explanations

offered

are

(a)

the

probability

of default

for

any

particular

borrower

increases as

the amount

borrowed

increases

(see Stiglitz 1970, 1972;

Marshall Freimer

and

Myron Gordon;

Dwight Jaffee;

George Stigler),

or

(b)

the

mix of borrowers

changes adversely (see

Jaffee and Thomas

Russell).

In these circum-

stances

we

would

not

expect

loans of differ-

ent

size

to

pay

the same interest

rate, any

more

than we

would

expect

two

borrowers,

one of whom has a

reputation

for

prudence

and

the other a

reputation

as a bad

credit

risk, to be able

to

borrow

at

the same interest

rate.

We

reserve the

term credit

rationing

for

circumstances

in which either

(a) among

loan

applicants

who

appear

to be identical some

2After

this

paper

was

completed,

our attention

was

drawn

to

W.

Keeton's

book. In

chapter

3 he

develops

an

incentive

argument

for

credit

rationing.

This content downloaded from 173.219.185.130 on Tue, 9 Sep 2014 11:54:41 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL.

71

NO.

3

STIGLITZ

AND

WEISS:

CREDIT

RATIONING

395

receive a

loan

and

others

do

not,

and

the

rejected

applicants

would

not

receive a

loan

even if

they

offered to

pay

a

higher

interest

rate;

or

(b) there are

identifiable

groups of

individuals in the

population

who, with

a

given

supply

of

credit, are

unable

to

obtain

loans

at

any interest

rate,

even

though with

a

larger

supply of

credit,

they

would.3

In

our construction of

an

equilibrium

model

with

credit

rationing,

we

describe a

market

equilibrium

in

which

there

are

many

banks and

many

potential

borrowers. Both

borrowers and banks seek

to

maximize

prof-

its,

the

former

through

their

choice of

a

project,

the

latter

through

the

interest

rate

they

charge

borrowers

and the

collateral

they

require

of

borrowers

(the

interest

rate

re-

ceived

by

depositors

is

determined

by

the

zero-profit

condition).

Obviously, we

are

not

discussing

a

"price-taking"

equilibrium.

Our

equilibrium

notion

is

competitive

in

that

banks

compete;

one

means

by

which

they

compete is

by

their

choice of

a

price

(interest

rate) which

maximizes their

profits.

The

reader

should notice

that in

the

model

pre-

sented

below

there are

interest

rates

at

which

the

demand

for loanable

funds

equals

the

supply

of

loanable funds.

However,

these are

not,

in

general,

equilibrium

interest

rates.

If,

at

those

interest

rates,

banks could

increase

their

profits

by

lowering

the

interest

rate

charged

borrowers,

they

would

do

so.

Although

these results are

presented

in

the

context

of

credit

markets,

we

show in

Section

V

that

they

are

applicable to

a

wide

class

of

principal-agent

problems

(including

those

describing

the

landlord-tenant

or

employer-

employee

relationship).

I.

Interest Rate

as

a

Screening

Device

In

this

section

we

focus

on

the

role of

interest

rates

as

screening

devices

for

dis-

tinguishing between

good

and

bad

risks.

We

assume

that

the bank has

identified a

group

of

projects;

for

each

project

6

there is

a

probability

distribution

of

(gross)

returns

R.

We

assume

for

the

moment

that

this

distri-

bution

cannot

be

altered

by

the

borrower.

Different

firms

have

different

probability

distributions of

returns.

We

initially

assume

that- the

bank is

able

to

distinguish

projects

with

different

mean

returns,

so we will

at

first

confine

ourselves

to

the

decision

prob-

lem

of

a

bank

facing

projects

having

the

same

mean

return.

However,

the

bank can-

not

ascertain

the

riskiness of

a

project. For

simplicity, we

write

the distribution

of re-

turns4

as

F(R,

0) and the

density

function

as

f(R, 0),

and we

assume

that

greater

6

corre-

sponds

to

greater

risk

in

the

sense

of

mean

preserving

spreads5

(see

Rothschild-Stiglitz),

i.e., for

,

>2,Jif

00

0

(1)

fRf(R,

01)

dR=

Rf(R,

2)

dR

then for

y

O,

(2)

j

F(R,01)dR>

jF(R,02)dR

If

the

individual

borrows the

amount

B,

and

the

interst

rate

is r,

then we

say

the individ-

ual

defaults

on

his

loan

if

the return

R

plus

the

collateral

C

is

insufficient to

pay

back

the

promised

amount,6

i.e.,

if

(3)

C+R<B(I +P)

3There is

another form

of

rationing

which

is

the

subject

of

our

1980

paper:

banks

make

the

provision of

credit

in

later

periods

contingent

on

performance

in

earlier

period;

banks

may

then

refuse

to

lend

even

when

these

later

period

projects

stochastically

dominate

earlier

projects

which

are

financed.

4These

are

subjective

probability

distributions;

the

perceptions

on

the

part

of

the

bank

may

differ

from

those of

the

firm.

5Michael

Rothschild

and

Stiglitz

show

that

condi-

tions

(I)

and

(2)

imply

that

project

2

has

a

greater

variance

than

project

1,

although

the

converse is

not

true.

That

is,

the

mean

preserving

spread

criterion for

measuring

risk

is

stronger

than

the

increasing

variance

criterion.

They

also

show

that

(I)

and

(2)

can

be

in-

terpreted

equally

well

as:

given

two

projects

with

equal

means,

every

risk

averter

prefers

project

I

to

project 2.

6This

is

not

the

only

possible

definition.

A

firm

might

be

said

to

be

in

default if

R

<

B(1

+

P).

Nothing

critical

depends

on

the

precise

definition. We

assume,

however, that if

the

firm

defaults,

the

bank has

first

claim

on

R+

C.

The

analysis

may

easily be

generalized

to

include

bankruptcy

costs.

However,

to

simplify

the

analysis, we

usually

shall

ignore

these

costs.

Throughout

this

section we

assume

that

the

project

is the

sole

project

This content downloaded from 173.219.185.130 on Tue, 9 Sep 2014 11:54:41 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

剩余18页未读,继续阅读

资源评论

pk_xz123456

- 粉丝: 2681

- 资源: 3706

上传资源 快速赚钱

我的内容管理

展开

我的内容管理

展开

我的资源

快来上传第一个资源

我的资源

快来上传第一个资源

我的收益 登录查看自己的收益

我的收益 登录查看自己的收益 我的积分

登录查看自己的积分

我的积分

登录查看自己的积分

我的C币

登录后查看C币余额

我的C币

登录后查看C币余额

我的收藏

我的收藏  我的下载

我的下载  下载帮助

下载帮助

前往需求广场,查看用户热搜

前往需求广场,查看用户热搜最新资源

- 基于redis全站抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于pybullet和stable baseline3 的法奥机械臂的强化学习抓取训练代码资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于Redis实现的一套分布式定向抓取工程。资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于RSS订阅自动抓取文章生成站点,这是个实验性功能。资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy+selenium+phantomjs的爬虫程序,用于抓取多个学校的学术报告信息资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy的danbooru图片抓取工具资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy的上市公司信息抓取工具资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于Scrapy框架,用于抓取新浪微博数据,主要包括微博内容,评论以及用户信息资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy的时尚网站商品数据抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy框架使用redis实现对shopee商城的增量抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于Scrapy爬虫对某守望先锋网站数据的动态抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于scrapy实现几大主流司法拍卖网站抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于Selelium图片抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于swoole扩展的爬虫,php多进程多线程抓取资料齐全+文档+源码.zip

- 基于Thinkphp5实现数据信息抓取、基于整理的API接口 + 招聘信息抓取(前程无忧智联招聘boss直聘拉勾网)数据接口 + 新闻分类(头条军事娱乐体

- FSCapture Ver. 8.9:屏幕截图与录制工具,图像编辑与快捷键支持,支持全屏、窗口、区域截图,滚动截图与视频录制,自动上传与FTP上传,适用于教学、设计、技术支持与文档制作

资源上传下载、课程学习等过程中有任何疑问或建议,欢迎提出宝贵意见哦~我们会及时处理!

点击此处反馈

安全验证

文档复制为VIP权益,开通VIP直接复制

信息提交成功

信息提交成功